Typology

Conversation

Scopes

Governance

When we see Collsacabra as a living organism, how can we heal it through practices that allow natural growth?

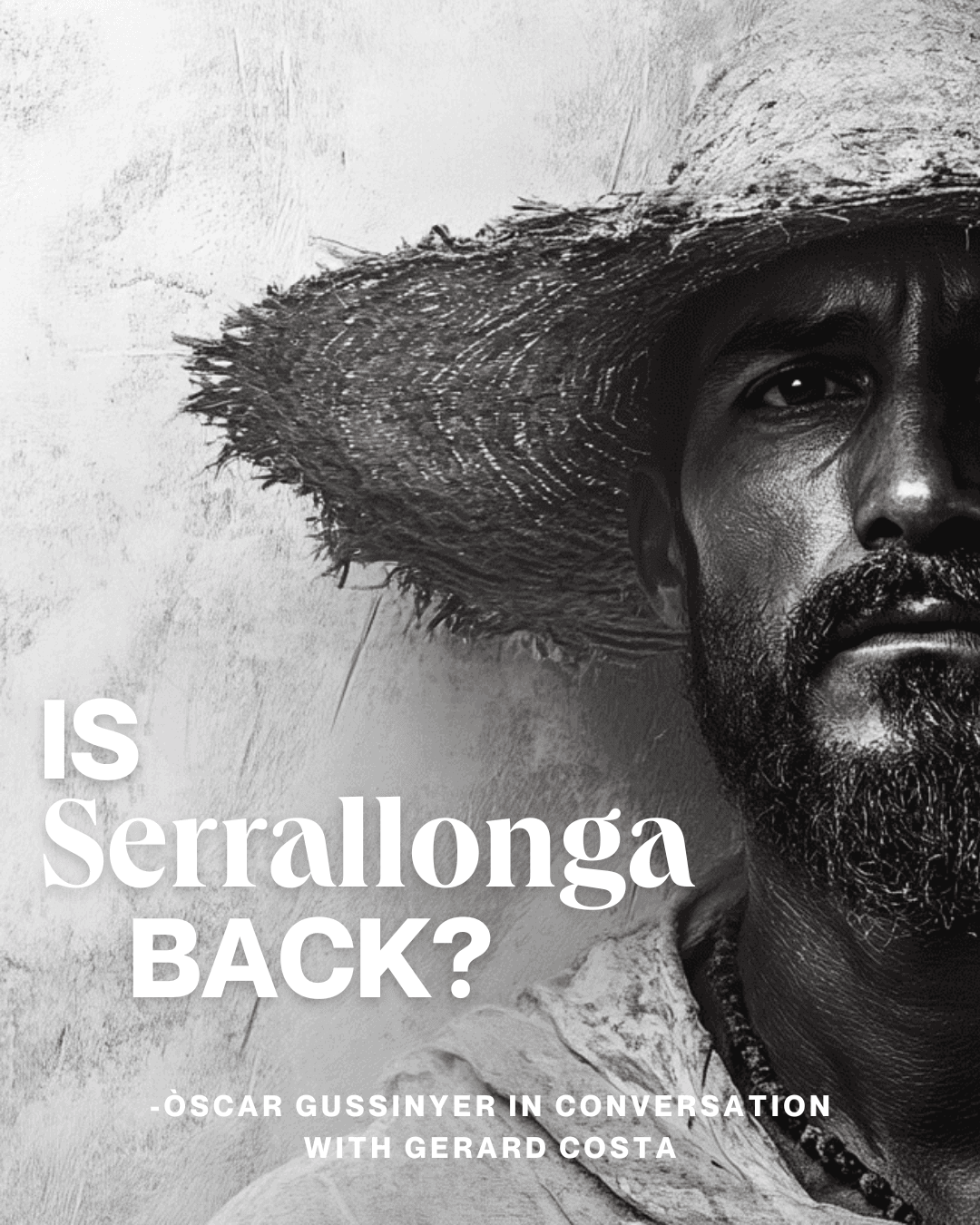

Today we have the opportunity to interview Gerard Costa, vice president of the second-degree cooperative Miceli Social and founder of Angigami. Gerard is a key figure in the transformation of rural territories, especially in Collsacabra, where he lives and works and has been leading several projects aimed at social and territorial regeneration. Through her work, she has helped to value local culture, sustainable management and global vision to face the challenges of rurality. His gaze is deeply influenced by ecosophy, ecosocial thinking and a work approach that integrates local knowledge with international experience. Its trajectory reflects commitment to sustainable development and the creation of support networks for rural communities.

Gerard, to start, could you tell us what Anigami is and what role do you play? How is this initiative articulated with the Miceli Social cooperative?

Gerard Costa: Anigami is an initiative with thirty years of travel and with many interconnected branches that was born to respond to the challenges we have as a society from various angles and one of them is the challenges we have in the rural communities and territories today. In fact, this line of work has taken weight in recent years to confirm that the economic growth model we have does not take into account the ecological and social dynamics of rural territories. Anigami brings a regenerative look, a workspace that integrates people, territory and nature to generate new, more sustainable and resilient life models. From Angigami, we seek to create a link between local initiatives and administrations and global ecosocial thinking to face the challenges facing us, such as climate change or gentrification of rural space.

In terms of Miceli Social, it is a second-degree cooperative with a number of entities, one of them Anigami, which allows us to join efforts for ecosocial transformation. In Miceli Social, we work transversally to create a cooperative model that faces the challenges of ruralism, such as depopulation and the need to recover local culture, always with collaboration and networking among the various agents of the territory. Miceli Social's work is closely aligned with the Angiami project, because we believe that transformative changes in communities cannot be achieved in isolation, but we need to create support networks that connect and share resources.

2. Talks of social and territorial regeneration. What exactly implies this concept in the case of Collsacabra?

Gerard Costa: Social and territorial regeneration is a concept that goes beyond sustainability. Sustainability is often left only in the environmental field or resource management, or simply to wash the face to an economy that is no longer extractive and speculative, but regeneration involves the balance of the entire community that cohabits a territory, the well-being of people and communities, and their ability to live in harmony with the principles that generate life. In Collsacabra, for example, this means not only taking care of natural spaces, but also of the people and biodiversity that cohabit this territory, creating spaces and dialogue where people can reconnect with the place and the community that welcomes us. This implies a systemic vision, where everything is connected: nature, local culture, economy, social relationships. Regeneration is therefore to create spaces of balance and harmony where the different elements feed back favoring life as it is.

In Collsacabra, for example, we still retain rooted values that are very inspiring, such as traditional agricultural activity, the link with our natural, identity and local culture landscapes, but we must also take into account the threats that affect the territory, such as the lack of generational relief, the difficulty of access to the land, the lack of housing for young people, massive tourism or gentrification. So regenerating means reconnecting with these essential values, but also knowing how to nurture them so that opportunities are created for people living here, avoiding the spoliation of resources and working for social and territorial justice. We must be aware that regeneration is not done from outside inwards, but from inside out and collectively, it is a change of ecosocial paradigm, it is necessary to involve people in the process of change and dispose of the tools to transform our territory.

3. In 2018 you saw that there were several problems in natural areas such as the Salt de la Foradada or the Morro de l'Abella. How did the need to do something before these challenges arise?

Gerard Costa: Yes, exactly. It was in 2018 that the mayors were aware that things were not good at Collsacabra. In particular, what was happening with such emblematic spaces as the Salt de la Foradada or the Morro de l'Abella, very emblematic natural spaces in the territory, within protective figures but without management organs. Collsacabra is a beautiful territory, but if we do not manage these spaces well, tourism ends up harming them. This natural space, very loved by the local population, was being solidified, when the alarm jumped we met with the mayors to search for solutions.

We designed a program, Natural Shrines, in order to make citizens aware of the need to preserve the values of the territories they visit, so we made thousands of interviews to the visitors of the spaces to extract the values that were going to look for, define the threats and collect a battery of proposals. This participatory task resulted in an awareness campaign that employed young people and that a few years later successfully validated in a new campaign of participation became municipal ordinance. Today Natural Shrines and the youth of the territories manage 10 natural spaces in Osona, and in 2023 we received international recognition.

This created a coordination space between the three mayors of the Collsacabra that had not been given before and from the good understanding began to happen things beyond each town, in the field of territory.

4. Are you talking about a joint territorial policy? What would be the first concrete action you proposed to better manage the territory?

Gerard Costa: Well, the first to emerge from these meetings with the mayors was the lack of this perspective of “Collsacabra” as a whole territory, of bioregion, far beyond the policies of each municipality. We were also aware of the need to properly plan and manage the public use of our natural landscape. So I asked two good friends to help us make an initial diagnosis: Josep Maria Mallarach, from Olot, renowned international consultant and Josep Gordi, geographer, who was then Dean of the Faculty of Letters of the University of Girona.

When we analyzed the Collsacabra, we discovered a living territory, inhabited, with beautiful geography and a great biodiversity. A systemically interconnected territory with the neighbouring territories, with tourism, with development, with enormous potential, but also subjected to certain pressures to be managed. The great conclusion of this diagnosis was that Collsacabra was in a maturation phase, but without a clear strategy or a vision of the future. So the first thing we proposed was to develop a strategic plan, which was not a formal document, but a vision of the future, made from within, with the active participation of the locals and the involvement of the administrations, but especially with the view of the natural and cultural values that define this territory.

5. What difficulties did you find when making a proposal with as much weight as this one, and how did you confront them?

Gerard Costa: The difficulty was to work on a vision of the future as a strategic plan, but without it being a strategic plan defined by experts such as passing, a 300-page document that ends in a drawer, but to find the way to listen to the reality of the territory and its potential and to generate enough political confidence to open the gaze to a bioregional governance participated by local citizens and administrations.

Both Mallarach and Gordi had already warned us that so generics are usually the strategic plans executed by specialized agencies but without a real link with a certain territory. So what was necessary was not a document that defined the future of the Collsacabra but a coup de timó to include the same territory and its cohabitants in this privileged space as it is to define any where we want to go as a community, as we want to see in 10 years or in the future and buzz it together.

So we worked on this line, with a very organic format.

6. In your project, you had the collaboration of experts. How did you select these people and what each of them provided to the project?

Gerard Costa: The mayors commissioned me this challenge with a small budget with which I could gather a team of experts. He wanted to work with people who could bring an open look to the project, people with professional backgrounds linked to the territory and with a capacity to cross concepts. I hired Josep Maria Mallarach, by geographical proximity and who gave a global vision and experience to many places in the world about how to cohabit the land, I also chose Jordi Pigem, a philosopher linked to Tavertet with a deep connection to ecosophy and the vision of nature that Panikkar proposed. I also had Guillem Mas of the Associació Paisatges Vius, de l'Esquirol, to include a naturalistic vision, and with Estel Vilar de Cantonigròs, a very sensitive person specialized in the Chinese tradition that provided a vision of the territory as a living organism, interconnected with energy and biodynamics of its own, and myself as a link.

The document that arose was a simple positive and negative view of what we could become in the future within a context of global political crisis, somehow allowing us to visualize where we were and the various scenarios that could be developed, and it was clear to encourage a binding citizen consultation with the aim of launching a bioregional governance structure capable of working together with the local administrations towards a vision of future shared throughout the territory.

7. How did you get mayors to accept the proposal to create a territorial policy?

I think the circumstances helped, we were in the pandemic and in that global context your neighbors were your best allies. The mayors initially had no joint vision of the Collsacabra, but they soon felt very comfortable working together. The predisposition of the three mayors was a key element. The vision of the future was very well received, mayors, councillors and technicians made it theirs and a compromise agreement was signed as a territory in Cantonigròs that placed the three councils to carry out the proposal. I remember that we also made a meeting with the mayors of the neighbouring territories that are part of the geographical Collsacabra such as the Vall d'en Bas, Sant Feliu de Pallerols, les Planes d'Hostoles and Susqueda to generate a fabric of alliances and support in shared challenges. There began a new territorial policy, on its own, emerged an alliance.

The next step was to summon the people of the territory and to initiate a citizen consultation, by areas of interest or tables of work that in a stable way are involved and lead their own vision of the future for their territory.

I asked Manel Buch for help, a well-known filmmaker based in Cantonigròs, and we recorded interviews with the key agents of the territory to share the video messages in the Collsacabra networks on topics that concern citizens with the aim of generating an unstoppable participatory wave. The mayors sought funding from the Diputació de Barcelona to start the consultative and participatory campaign. 8. When you talk about creating a "vision of the future" for Collsacabra, what does that mean exactly?

A "vision of the future" for Collsacabra is to create a sustainable and regenerative approach to the territory, which integrates the values that define it and enhances it. We began working on the basis of identifying the elements that made Collsacabra an inhabited, living and unique landscape and that allowed us to maintain our identity, without falling into gentrification or uncontrolled tourism. This work includes understanding what threats and opportunities are, how agricultural, livestock, tourism and forestry activities can be managed in a balanced way and bringing value to the territory, and how all this articulates within the larger system. Always from the participation and involvement of citizens and entities of the territory. This is not only an economic development plan, but also the social and environmental sustainability of the area, always seeking a model of maximum resilience for the future.

9. What was the next step after presenting the "Future Vision" to the mayors? What happened after this initial moment?

This official statement marked the beginning of the next step, which was the citizen involvement. A year later the Diputació de Barcelona facilitated the budget by a participatory process that according to the standards of a framework agreement, which defines which companies execute these projects, the external agency EspaiTres led the process. A participatory work was proposed in order to agree to the future vision of Collsacabra with neighbours. The goal was that citizenship could bring ideas so a group of work tables were proposed to collect the main challenges and proposals of action from participation in the three peoples. The involvement and participation of citizens was low, the lack of participatory culture and the difficulties in working collectively were reefs that were not resolved. Many people were not used to thinking together, to cooperate and to share resources and knowledge between peoples and sectors. He also lacked participation from young people.

Many brilliant proposals were collected that generated a very enriched and extensive document, but difficult to apply because the process culminated in the tables dissolved and without effective resources to coordinate and implement the actions.

At that time, citizen participation was understood as a goal, as a way to permeabilize democracy and not as much as a form of citizen involvement, of participatory culture. What had been projected since the Future Vision was to involve the community not only to project but to articulate proposals in an organized and collective way alongside its city councils. This did not happen and the process ended with the formal document. Today participation has already been understood as a working tool for a larger and more transformative purpose.

10. What were the main failures of this process and what can be learned from it for the future?

Well, I would not say failure but a first step towards this culture of participation necessary to transform our communities into people involved in the devancing of their territory and their cultural landscape with a look at the future. Lacks were lack of cohesion, disconnection with local reality and the absence of resources to articulate the process. Although the final document contained courageous proposals, the fact that it was not actively involved in citizenship or generating concrete actions proved to be a loss of opportunity. What can be learned from this experience is that participation processes cannot come from outside, but real alliances with the community and a shared learning approach capable of transforming. People in the territory must feel part of this process from the beginning, lead it with a methodology appropriate to their interests, language and needs. The most important thing is to understand that participation should be more than an institutional "action"; it must be a continuous practice that involves not only collecting opinions, but also working together towards the common goal. Thus, the future must go through a collaborative management based on trust and shared work among all social, cultural, economic and institutional actors.

11. How did the creation of the Collsacabra Farmers' Table and what objectives did you seek to achieve with this space?

The creation of the Taula de la Pagesia and the Local Product of the Collsacabra emerged following a casual conversation with a village rancher on two particular topics. At a meeting in the Town Hall, the rancher was asked to make an agricultural shed, and I wanted them to connect water to the network in Les Comes, the farmhouse where we have the offices, without network water. We both left the city council without solutions. After this meeting, we realized that the two were alone, in similar situations of injustice and difficulties to manage our activities. I thought ours were generic problems of many farmers and people of the farmhouses and that if we were together, we could paint and become a valid interlocutor before the administrations. So, with this feeling of collaboration and union of forces and with the financing and support of Miceli Social, we created the Farmers' Table with the aim of bringing together all those who live in the peasantry, ranchers, farmers, producers and restaurateurs and those who had common shortcomings. With this table, we wanted to create a space of cooperation and be a strong interlocutor to the institutions, to be able to promote collective initiatives that benefit the three sectors involved. Thus, the Table was born to cover joint shortcomings and to give efficient answers to the social needs of the territory that were not covered.

12. What were the three main challenges that the Farmers' Table identified in its first meetings and what solutions were proposed?

At the first meeting of the Taula de la Pagesia, we were about 35 - 40 attendees from all the Collsacabra, identified three key challenges. The first was that the administrations did not understand us, that is, they are not connected to the local reality and do not understand or cannot articulate our specific needs. The second challenge was that we do not know enough between us, which made it difficult for cooperation and the creation of useful alliances to face the common challenges. The third challenge was that intermediaries, branded sales prices and took much of the profits. The solution we proposed was to establish a greater degree of communication and collaboration between ourselves, overcome individualism and work together. Thus, we began to propose concrete actions, such as establishing a shared workman, and also began to bring politicians, technicians and other social actors to see if we could establish the basis to solve these challenges together.

13. What was the response of institutional actors and how did their attitude influence the evolution of the Farmers' Table?

In the following meetings of the Farmers' Table, we invited technicians, politicians and other representatives of the three challenges they had emerged. Teresa Colell, responsible for the Strategic Plan of Food of Catalonia, Albert Puigvert, manager of the Association of Rural Initiatives of Catalonia, Margarida Feliu, vice president of the Regional Council of Osona and Abel Peraire, responsible for a livestock farm in Lluçanès with its own elaboration and distribution. The answer was very positive and inspiring, as we saw the potential to work together and that we could really do things to improve the territory. One of the key points arose when Teresa Colell, told us that the aid that the Generalitat allocates to ranchers did not arrive effectively because, as individual farmers, we were too small, but if we joined, we could opt for these aid and get resources. Thus, consensus was generated about the need to join us to be stronger as a group, and this opened the door to focus the detected shortcomings so we requested a help to make a feasibility study for a shared workman. However, not everything was easy, as we still found resistance to making concrete, collective and durable decisions, but it was a first step to establish a path of collaboration and union between us and institutions.

14. What was the main obstacle you encountered when you tried to create the shared workman, and how did this obstacle influence the project?

The main obstacle was bureaucracy and logistical difficulties that did not facilitate us. Having no own NIF, we joined with the Ramaders association of the Serra de Bellmunt, the neighbouring territory, to request help together. This caused the epicenter of the two territories to be the Plana de Vic and finally the workshop would have been installed in Manlleu, too far by both the farmers of Collsacabra and those of Bellmunt, so the project did not have continuity although the lack persists.

Despite not being able to carry out the workshop, teamwork and the creation of the Taula de la Pagesia allowed us to generate knowledge and experience to continue advancing. Every year we organize a technical conference where we invite inspiring projects from other rural territories such as the association "Terra de Masies" of Solsonès or La Fira del Corder of the Association of Ramaders of Pallars.

Currently, we are re-activating the project of the workman shared in the Collsacabra from the entities and the city councils seeing how to overcome the lack of structure and financing.

When we understand the Collsacabra as a living organism, each action, from the care of the territory to the transformation of our individual practices, becomes a bridge towards collective regeneration, where the interconnection between nature and people guides the way to an equitable and resilient community.

15. How do you imagine the future of Collsacabra and what actions are necessary to ensure its long-term sustainability?

The future of Collsacabra must go through a model of co-operation and cohesion among all actors in the territory from a policy involved in the bioregional level. What we are trying to build is a resilient system, with a strong local economy and linked to the values of the land and the local product. To achieve this, we have to continue working from the actions that we have already started, but with a greater long-term vision. It is important that we create synergies with other actors, whether in the same region or other areas, because a project like Collsacabra cannot be conceived in isolation. To ensure the sustainability of the territory, an ecosocial transition is necessary, a strategy that includes the creation of shared infrastructures, the impulse of sustainable agricultural and livestock projects, and the preservation of natural landscapes, while maintaining the balance between economy, local culture and nature. It is also essential to enhance the ability of local communities to face challenges, with the active involvement of young people and women in the process. Finally, transparency and efficiency in resource management, as well as the creation of collaboration networks between different sectors, administrations and institutions, will be key to ensuring that Collsacabra is still an example of regenerative bioregionalization.

16. How did the creation of the Collsacabra Farmers' Table and what objectives did you seek to achieve with this space?

The creation of the Taula de la Pagesia del Collsacabra emerged from a casual conversation after a meeting with a rancher and Gerard of Angiami, on two topics related to the difficulties of the territory. At a meeting in the Town Hall, a rancher wanted an agricultural shed, and Gerard wanted to get water to the network for Les Comes, an area where there was no water. After this meeting, we realized that we both found ourselves in similar situations of injustice and difficulties to manage our activities. We met at the bar and realized that we were alone in our requests, and if we were together, we could be a valid interlocutor before the administrations. So, with this feeling of collaboration and joining forces, we created the Farmers' Table with the aim of bringing together those who lived in the peasantry, the ranchers, the farmers, and those who had common shortages. With this union, we wanted to create a space of cooperation and be a strong interlocutor to the institutions, to be able to promote collective initiatives that benefit all the sectors involved. Thus, the Table was born to cover joint shortcomings and to give efficient answers to the needs of the territory.

17. What were the three main challenges that the Farmers' Table identified in its first meetings and what solutions were proposed?

At the first meeting of the Farmers' Table, we identified three key challenges. The first was that the administrations do not understand, that they are not connected to the local reality and do not understand our specific needs as farmers and inhabitants of the territory. The second challenge was that we did not know enough between us, which made it difficult for cooperation and the creation of useful alliances to face the common challenges. The third challenge was that intermediaries, those companies or external actors, took advantage of our lack of organization and charged us with costs or made us unable to advance as a collective. The solution we proposed was to establish a greater degree of communication and collaboration between ourselves, overcome individualism and work together. Thus, we began to propose concrete actions, such as establishing a shared workman, and also began to bring politicians, technicians and other social actors to see if we could establish the basis to solve these challenges together.

18. What was the response of institutional actors and how did their attitude influence the evolution of the Farmers' Table?

In the first meetings of the Farmers' Table, we invited several institutional actors such as the representatives of the Council, technicians and other politicians. The answer was, in many cases, positive, as they saw the potential to work together with us and realized that we could really do things to improve the territory. One of the key points that arose was when Teresa Colell, an institutional representative, told us that the aid that the Diputació destined to the ranchers did not arrive effectively because, as a collective, we were too small and individual. But if we joined, we could optimize these aids and get more resources. Thus, a kind of consensus was generated about the need to join us to be stronger as a group, and this opened the door to get more aid and resources. However, not everything was easy, as we still found resistance to making concrete and durable decisions, but it was a first step to establish a path of collaboration and union between us and institutions.

19. What was the main obstacle you encountered when you tried to create the shared workman, and how did this obstacle influence the project?

The main obstacle we found when we tried to create the shared workshop was that although we had the theoretical support of the Diputació and other actors, the reality was that bureaucracy and logistical difficulties did not make things easier. One of the first problems was that the Taula de la Pagesia had no own NIF, which forced us to search for another entity with a NIF to submit the request for aid. This lack of initial formalization generated a mismatch in the process. We also tried to establish the workshop in a more centralized place, but ranchers were not willing because they felt that the location, like Manlleu, did not offer them the benefits we expected. This led to a second mismatch in our strategy. Despite these difficulties, we continued to work and maintain the project alive with the help of other organizations such as Arca, and we continued to hold meetings and work together on other actions to find solutions. Despite not being able to carry out the workshop, teamwork and the creation of the Taula de la Pagesia allowed us to generate knowledge and experience to continue advancing.

20. How do you imagine the future of Collsacabra and what actions are necessary to ensure its long-term sustainability?

The future of Collsacabra must go through a model of cooperation and cohesion among all actors in the territory. What we are trying to build is a resilient system, with a strong local economy and linked to the natural environment. To achieve this, we have to continue working from the actions that we have already started, but with a greater long-term vision. It is important that we create synergies with other actors, whether in the same region or other areas, because a project like Collsacabra cannot be conceived in isolation. To ensure the sustainability of the territory, a strategy that includes the creation of shared infrastructures, the impulse of sustainable agricultural and livestock projects, and the preservation of natural spaces, while maintaining the balance between economy, local culture and nature. It is also essential to enhance the ability of local communities to face challenges, with the active involvement of young people and women in the process. Finally, transparency and efficiency in resource management, as well as the creation of collaboration networks between different sectors, will be key to ensuring that Collsacabra remains an example of regenerative bioregionalization.

The Collsacabra is like a river that flows silently, with each drop that combines with the others to form a stream that gently transforms the landscape, adapting and constantly renewing, guided by the harmony of its waters.

Conclusion

The role of Miceli Social in the regeneration of ruralities such as Collsacabra

The transformation model that is being deployed in Collsacabra, as explained by Gerard Costa, is a clear example of how rural territories can be managed in a regenerative and adaptive way, working from within, with the active collaboration of all local agents and the incorporation of visions and diverse knowledge. The creation of participation spaces such as the Farmers' Table and strategies to promote local cooperation and sustainability show a path towards regenerative bioregionalization that has been proven effective in the context of the Collsacabra.

This approach, however, is not limited only to this territory. Miceli Social, of which Gerard is vice president, is a second-degree cooperative that aims to accompany social and environmental change projects in rural areas. His accumulated experience through processes such as Collsacabra positions them as a fundamental actor in the generation of similar changes in other rural contexts in Catalonia and beyond.

What makes Miceli Social unique is its ability to unite efforts between different social, economic and political agents to create territorial models that are resilient and fair. Its second-degree cooperative approach allows working transversally and integrating different sectors of society: from farming and agriculture to sustainable tourism and forest management, while maintaining balance with nature and promoting the regeneration of natural resources.

Gerard and Miceli Social's role in this process is not only the role of facilitators, but also the role of generating spaces where different local voices can be heard and where a common vision of the future can be woven. Thus, Miceli Social can be a key piece for those rural territories that want to undertake regeneration and transition processes towards sustainable and fair models. Through collaborative work, the formation of local teams and the impulse of projects that integrate social, economic and environmental sustainability, Miceli Social offers the necessary tools for other ruralities to jump towards real and effective regeneration.

Miceli Social has the potential to be a reference in the creation of sustainable and regenerative development strategies in other rural areas that want to address global challenges from a local and community perspective. With this model, deep and sustainable changes can be generated that not only transform communities but also contribute to the construction of a more balanced and resilient future for all.

In addition, this process encourages cultural change in communities, creating a sense of belonging and shared responsibility. Communities become active agents of regeneration, preparing to face future changes with long-term strategies.

This application of bioregionalization increases territorial resilience, allowing the territory to regenerate through its own dynamics. The more we understand the interrelationships of the site, the more capacity we have to face global and local challenges, creating long-term solutions and helping communities to thrive.

In short, bioregionalization is a process of identifying active patterns and regeneration, which allows us to take advantage of the inherent potential of sites. This not only helps to face immediate challenges, but also opens the way to a more adaptive and resilient future. Crisis become opportunities for evolution and prosperity.